Situational Action Theory (SAT)

Situational Action Theory

Situational Action Theory (SAT) is a general, dynamic and mechanism-based theory of crime and its causes that analyses crime as moral actions. SAT proposes to explain all kinds of acts crime (hence, general), stresses the importance of analysing the person-environment interaction and its changes (hence, dynamic), and focuses on identifying key basic explanatory processes involved in crime causation (hence, mechanistic).

SAT was developed to overcome the generally observed fragmentation and poor integration of key criminological insights and provide a comprehensive theoretical framework to analyse crime and its causes (Wikström, 2004; Wikström, 2017:504-509). In particular, it aim to address the following common problems in criminological theorising; the lack of a clear and shared definition of crime (the need to clearly specify what a theory of crime causation aim to explain); the poor integration of the role of people and places and, crucially, their interaction in crime causation (the need to for a dynamic explanation of crime and its changes); the frequent confusion of causes and correlates (the need to move beyond a risk factor [predictor oriented] explanatory approach and to focus on the role of basic causal processes); the lack of an adequate action theory (the need to understand what moves people to action in order to identify what macro-social and developmental factors and processes are relevant and important in crime causation).

SAT was initially developed during the late 1990s and early 2000s. The first outline of the theory in English was published in 2004 and it have since been further advanced, extended and refined over the last 15-years (e.g., Wikström, 2004; 2005; 2006; 2010; 2011; 2017; Wikström et al, 2012:3-43; Wikström & Treiber, 2018).

Basic assumptions

Situational Action Theory is grounded in the following basic assumptions about human nature, society, crime and the causes of action.

1. People are essentially rule-guided creatures

People express their desires, and respond to frictions, within the context of rule-guided choice

2. Social order is based on shared rules of conduct

Patterns in human behaviour is based on rule-guided routines

3. People are the source of their actions

People perceives, choose and execute their actions

4. The causes of action are situational

People’s particular perception of action alternatives, process of choice and execution of action are triggered and guided by the relevant input from the person-environment interaction

5. Crimes are moral actions

Crimes are ‘actions that break rules of conduct (stated in law) about what is the right or wrong thing to do in a particular circumstance’ and are best explained as such.

The Comprehensive Framework

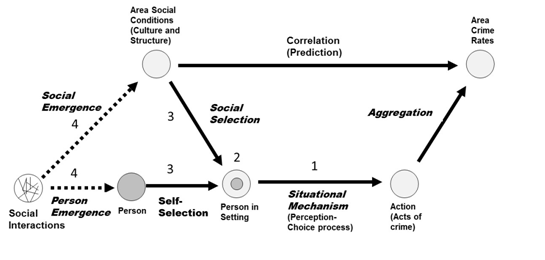

Situational Action Theory is built around three kinds of basic explanatory mechanisms; situational, selection and emergence mechanisms (for further details see, e.g., Wikström, 2017:513-516; Wikström, 2018).

1. The situational mechanism (the perception-choice process) explains why crime events happens.

2. The selection mechanisms (processes of social and self-selection) explains why criminogenic situations arise.

3. The mechanisms of emergence (person and social emergence) explains why people (through psychosocial processes) and places (through socio-ecological processes) become different in aspects relevant to crime causation

Figure 1. SAT’s comprehensive explanation of crime illustrated.

Source: Modified from Wikström 2011:68.

How the basic mechanisms relate are illustrated in Figure 1 and summarised below:

1. Crime events are ultimately an outcome of a perception-choice process

2. The perception-choice process is initiated and guided by relevant aspects of the person-environment interaction.

3. Contemporaneous processes of social and self-selection place kinds of people in kinds of settings (creating particular kinds of interactions of which some are criminogenic).

4. What kinds of people (with what kind of crime propensities) and what kinds of environments (with what kind of criminogenic inducements) are present in a jurisdiction is a result of historical processes of personal and social emergence.

The Situational Mechanism – The PEA hypothesis

At the core of Situational Action Theory is the situational model and the PEA hypothesis that explains why crime events happens (for further details about its foundation see Wikström 2006; for its most recent formulation and details see Wikström 2017: 511-513; Wikström 2018). The core propositions is that

People ultimately commit acts of crime because they find them acceptable in the circumstance (and there is no relevant and strong enough deterrent) or because they fail to act in accordance with their own personal morals (i.e., fail to exercise self-control) in circumstances when externally pressurised to act otherwise.

SAT maintain that acts of crime are an outcome of the convergence of and interaction between people’s crime propensities and places criminogenic inducements. According to SAT, people’s crime propensities depends on their law-relevant personal morals and abilities to exercise self-control and places criminogeneity depends on their law-relevant moral context (moral norms and their enforcement) of the opportunities and frictions they provide.

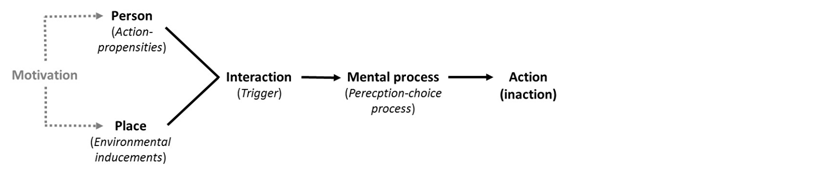

Figure 2 The key steps in the action process.

Source: Wikström, 2018

The PEA hypothesis (P x E →A)specifically proposes that an act of crime (A) is an outcome of the perception-choice process (→) initiated and guided by the interaction (x) between people’s crime propensities (P) and the immediate environments criminogenic inducements (E) in response to a specific motivation (Figure 2). Acts of crime are thus ultimately an outcome of specific combinations of certain kinds of people (propensities) in certain kinds of places (inducements).

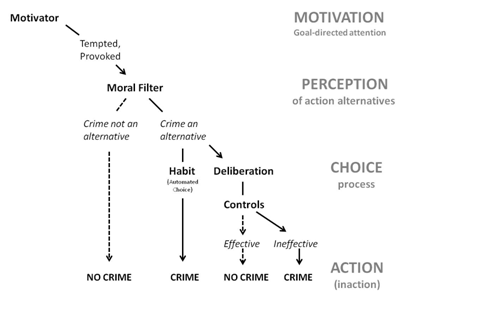

Figure 3 Overview of the key steps in the perception-choice action process

Source: Wikström 2017:511

The perception-choice process include three key explanatory elements, ‘motivation’, ‘the moral filter’ and ‘controls’ as illustrated in Figure 3. In brief, the argument runs as follows;

- The action process is initiated by a motivator (a temptation or provocation) which provide goal-directed attention. Motivation is a situational concept. Motivation is a necessary but not sufficient explanation of action.

- What action alternative/s a person sees in relation to a specific motivator – and whether this include an act of crime or not - depends on the moral filtering (which is a consequences of the application of a person’s personal morals to the moral context of the motivator). The moral filter is a situational concept.

- If the person do not see an act of crime as an action alternative in response to a particular motivator there will be no crime. Importantly, the person do not choose not to commit an act of crime. She or he simply do not see an act of crime as an action alternative and the process of choice is therefore irrelevant. Perception of action alternatives is a more fundamental factor than the process of choice in the explanation of why crime events happen.

- A choice is the formation of an intention to act in one way or another. Choice is a situational concept. Whether or not a person who sees an act of crime as an action alternative in response to a particular motivator will commit an act of crime depends on the process of choice. Depending on the circumstances, the process of choice can either be predominantly habitual or rational deliberative in nature.

- When people act out of habit they essentially react (in a stimulus-response fashion) to environmental cues. They only perceive one potent action alternative (although they are likely to be loosely aware “in the back of their minds” that there are other alternatives). Habitual choices are oriented towards the past as they involve drawing upon past experiences to guide current (automated) choices. Habits are created by repeated exposure to similar circumstances and most likely when people are in familiar circumstances with congruent rule guidance (or experience high levels of emotion or stress).

- When people perceive more than one potent action alternative the process of choice become rationallydeliberative. Deliberations are oriented towards the future and an assessment of the best possible outcome (an act of crime will be chosen if that is considered the best option). According to SAT, the best option is typically the one considered in the circumstance to be the most viable and morally acceptable alternative to satisfy a desire, honour a commitment or respond to a friction (not necessarily the one that is seen to maximise personal advantage or gain). When people deliberate they exercise “free will” within the constraint of perceived action alternatives. The level of deliberation may vary strongly depending on the perceived importance of the choice. Rational deliberation is most common when people operate in unfamiliar circumstances and/or there is conflicting rule-guidance

- Controls are influences that oppose something in support of something else. Control is a situational concept. Controls are irrelevant as an explanation of crime events in cases in which people do not see crime as an action alternative or commit acts of crime out of habit. Only when people deliberate and there is conflicting rule-guidance do controls affect the outcome. Effective controls prevent a person from conducting an act of crime she or he otherwise would have engaged in.

- Controls may be internal (self-control) or external (deterrence) in origin. Self-control and deterrence are situational concepts. Self-Control is ‘when a person’s succeed in withstanding external pressure to engage in an act of crime that conflicts whit her or his own personal morals‘. Deterrence is ‘when a place (immediate environment) – through threats of immediate or future consequences - succeed in making a person to refrain from an act of crime they otherwise would have engaged in’. SAT clearly differentiate analytically between ‘exercising control’ (situational) and the ‘capacity for control’(characteristic). The person’s ability to exercise self-control is a personal characteristic. A place capacity to enforce its moral norms is a place characteristic.

The principles of moral correspondence and the conditional relevance of controls.

Two important principles in SAT concerning the interaction between morality and controls in the process of choice is the principle of moral correspondence and the principle of the conditional relevance of controls (e.g., Wikström, 2010:233-234). The principle of moral correspondence state that if there is a close correspondence between a person’s personal morals and the moral norms of the setting in which they take part they are likely to act in accordance with this (which depending on the content of the rule-guidance may either encourage or discourage getting involved in an act of crime).

The principle of the conditional relevance of controls states that a person’s ability to exercise self-control will impact the outcome in cases in which her or his personal morals discourage but the moral norms of the setting encourage an act of crime (a strong ability to self-control may prevent crime), and that the settings capacity to deter will affect the outcome in cases in which the person’s personal moral encourage but the moral norms of the setting discourage an act of crime (a strong deterrence may prevent crime).

The DEA model – explaining the dynamics of criminal careers

The Developmental Ecological Action model (The DEA model) was developed as an application of SAT to the study and analyses of the dynamics of stability and change in people’s criminal careers (originally presented in Wikström, 2005 and refined in Wikström & Treiber, 2018 – see these publications for the basis and details of the key arguments).

Given that the fundamental proposition of SAT is that the causes of crime are situational and can be explained as an outcome of the convergence of and interaction between crime prone people and criminogenic places, it follows that changes in people’s crime involvement are essentially a result of changes in their crime propensities and/or exposure to criminogenic places.

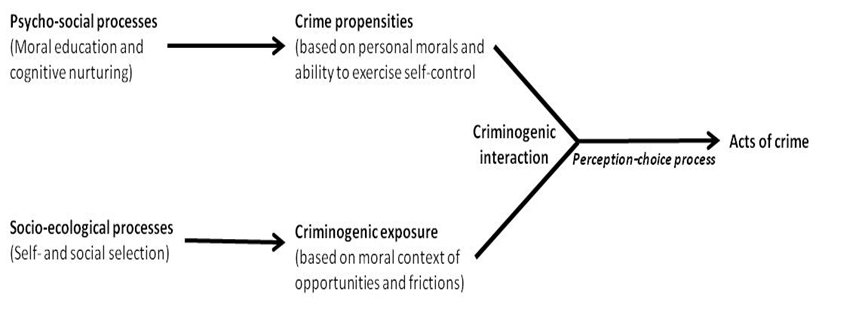

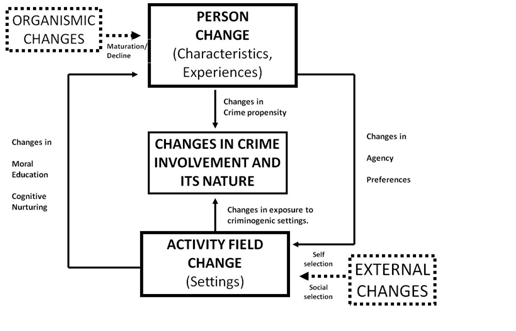

The basic idea is that people’s development and change of their crime propensity (based on their personal morals and ability to exercise self-control) is an outcome of psychosocial processes of moral education and cognitive nurturing, and that their exposure to criminogenic settings (moral contexts of opportunities and frictions) and its changes is an outcome of socio-ecological processes of social and self-selection (Figure 4).

Figure 4 The drivers of individual change in crime involvement according to SAT

The full DEA model is presented in Figure 5. The proposed sources of change and how they relate in the DEA model is summarised in the seven propositions stated below (see further Wikström & Treiber, 2018).

Figure 5 The full Developmental Ecological Action (DEA) model.

Changes in crime involvement and its nature

1. Changes in people’s crime involvement, its nature and frequency, are mainly driven by changes in people’s crime propensities and their exposure to criminogenic settings (because these change the nature and frequency of the criminogenic interactions people experience).

Personal changes (influencing crime propensities)

2. Organismic changes occur as a result of general processes of biological maturation and decline or instances of illness and injury which may lead to changes in basic personal capacities (to understand and apply rules and exercise agency and self-control) or the ability for those capacities to be changed.

3. Changes in people’s crime propensities are mainly driven by relevant aspects of their moral education and cognitive nurturing (facilitated or impeded by relevant aspects of organismic change) because people’s crime propensities are largely based on their law-relevant personal morals and ability to exercise self-control.

4. Changes in people’s moral education and cognitive nurturing are mainly driven by changes in their activity field (exposure to particular configurations of settings) because people develop and change their propensities in response to the settings in which they take part.

Activity field changes (influencing criminogenic exposure)

5. Changes in people’s exposure to criminogenic settings (its nature and frequency) are mainly driven by changes in their activity fields as a result of changes in processes of self-selection (based on agency and activity preferences) and social selection (based on societal rules and resource distributions). A person’s activity field is the configuration of settings in which she or he typically takes part.

6. Changes in people’s agency (powers to make things happen) are driven by organismic changes and changes in their human, financial and social capital, while people’s development of and changes in activity preferences are driven by their positive and negative experiences of particular activities.

7. External changes (e.g., as a result of political, economical, and technological changes) may impact the nature and frequency of available settings (in a jurisdiction) or the rules regulating and access to resources relevant to a particular person taking part in particular settings.

A note on the role of macro-social factors in crime causation

A core argument of SAT is that the role of macro-social factors such as inequality and segregation in crime causation are best analysed as potential causes of the causes (e.g., Wikström, 2011) and in terms of processes of social selection that influences how different kinds of people are exposed to different kinds of places. SAT proposes that one major source of variation in crime involvement between people, and categories of people, for example, by gender, ethnicity and social class, is due to differences in social selection. Some people are more often than others exposed to criminogenic settings (Wikström et. al., 2012). In the longer term, people’s crime propensities are dependent on their exposure to settings that influence the development (and change) of their law-relevant personal morals and abilities to exercise self-control. However, SAT also make a strong argument that historic (longer-term) influences on people’s crime propensities, and concurrent influences on their exposure to criminogenic settings by processes of social selection preferably should be analysed in conjunction with the role of people’s processes of self-selection. People are not purely marionettes at the mercy of social forces (albeit, this vary among people - and during people’s life-span - some have a stronger agency than others).

References:

Wikström P-O (2004). Crime as Alternative. Towards a Cross-level Situational Action Theory of

Crime Causation. In (Ed) J. McCord: Beyond Empiricism: Institutions and Intentions in the Study of Crime. Advances in Criminological Theory. New Brunswick. Transaction.

Wikström P-O (2005). The Social Origins of Pathways in Crime. Towards a Developmental

Ecological Action Theory of Crime Involvement and its Changes. In (Ed) D.P. Farrington: Integrated Developmental and Life-Course Theories of Offending. Advances in Criminological Theory. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Wikström P-O (2006). Individuals, Settings and Acts of Crime. Situational Mechanisms and the

Explanation of Crime. In (Eds) Wikström P-O & Sampson Robert. J. The Explanation of Crime: Context, Mechanisms and Development. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Wikström P-O (2010). Explaining Crime as Moral Action. In (Eds) S. Hitlin & S. Vaysey: Handbook of the Sociology of Morality. New York. Springer verlag.

Wikström P-O (2011) Does Everything Matter? Addressing the Problem of Causation and Explanation in the Study of Crime. In (Eds) McGloin J M, Sullivan C. J & Kennedy L. W. (Eds): When Crime Appears: The Role of Emergence London. Routledge.

Wikström P-O (2017) Character, Circumstances, and the Causes of Crime. In (Eds) Liebling A., Maruna S. & McAra L.: The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Oxford. Oxford. University Press.

Wikström (2018). Situational Action Theory. Oxford Research Encyclopedia (ORE) of Criminology and Criminal Justice ( http://criminology.oxfordre.com/ ) . Oxford University Press.

Wikström P-O & Treiber K. (2018) .The Dynamics of Change. Criminogenic Interactions

and Life-Course Patterns of Crime. In (Eds) D. P. Farrington, L. Kazemian & A. Piquero: The Oxford Handbook of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Wikström P-O, Oberwittler D., Treiber K. & Hardie B. (2012). Breaking Rules. The Social and Situational Dynamics of Young People’s Urban Crime. Oxford. Oxford University Press.